The Acadians in Exile The Return: 1755-1766

From the blog at http://JohnWood1946.wordpress.com

Mapannapolis follows this blog. We’re delighted to re-post this story here.

The Acadians in Exile—The Return. 1755-1766

I like writing that is full of facts, and without sentiment. John Herbin disagreed, however, and the following is his very sentimental telling of the aftermath of the Expulsion. And how else was he to tell the story? The facts were awful, and the people were his ancestors. The following is from one chapter of his Grand Pré, a Sketch of the Acadian Occupation of the Shores of the Basin of Minas, Toronto, 1898.

The Grand Pré National Historic Site

From Parks Canada

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

The Acadians in Exile—The Return. 1755-1766

We have shown [referencing the author’s book] how awful in its results was the deportation, both in robbing this country of a prosperous people, and in depriving those people of a home, and separating families and kindred in widely divided places in New England. Lawrence, the chief mover in the shameful act, gave twenty thousand acres of land to each of the chief agents. He himself had the handling of the wealth in products and livestock which the Acadians left, and the lion’s share of that wealth was his. The deportation was worked out in a most heartless manner, to prevent, if possible, the reunion of families, and their return to Acadie. A great many died in a few years, on account of the hardships they had to bear. A small proportion of them found their way back to their former homes. Their descendants number thousands today, but the great purpose of the deportation was carried out; their land was offered to English settlers, and finally taken by them; and the wealth of the Acadian’s was devoted to others. In the course of years many documents that would throw light on the events of 1755 were lost or, as many think, destroyed. The recovery of papers in England led to the reconstruction of Acadian history, and has changed the character of many events of that time. A grudging justice is being done to the unfortunate people who had suffered so much at the hands of merciless men.

It is not my intention to follow the Acadians into exile. The story of Minas is ended. “Dispersed by the orders of Lawrence, decimated by malady, deprived of spiritual succor and human consolations, received with mistrust and contempt, placed in a desperate situation without any visible way out, crushed under the burden of an overwhelming woe, could they again become attached to life, set themselves once more to work and resume their former hopes?”

In other parts of the country the Acadians met the same fate as those of Minas. Between 1755 and 1763, it is believed that fourteen thousand out of the eighteen thousand Acadians of the maritime country were removed. Of these at least eight thousand perished through grief, destitution, disease and other causes.

Only a small number of the people were put ashore in the northern ports of New England, except at Boston, where two thousand were landed. New York and Connecticut received, respectively, two hundred and three hundred. The remainder were distributed in Pennsylvania, Maryland, the Carolinas and Georgia. In Philadelphia they were at first forbidden to land, but after being over two months on the vessels, the three overcrowded ships gave up their unhappy freight. The last reference to these is in the city records of 1766, when a petition was tabled which asked for the payment for coffins provided for the French Neutrals. Death had reduced them from four hundred and fifty to two hundred and seventeen.

South Carolina furnished the fifteen hundred Acadians who landed there, with vessels to return. After many hardships and misfortunes, they reached St. John River, on the Bay of Fundy, reduced to half their number.

Those who reached Georgia were again banished. They were permitted to make boats, and in these they made their way back as far as Massachusetts, when an order from Lawrence caused their boats to be seized and themselves to be made prisoners.

Others made their way to Louisiana and settled. Their numbers increased by the arrival of others till 1788, from San Domingo, Guiana, the ports of New England, and from France. Their descendants now [1898] number about forty thousand.

Of those who landed in Massachusetts, Hutchinson, the historian, says: “It is too evident that this unfortunate people had much to suffer from poverty and bad treatment, even after they had been adopted by Massachusetts. The different petitions addressed to Governor Shirley about this time are heartrending.” This condition gradually lessened till they were able to leave the State for Canada.

Virginia refused to accept the fifteen hundred who were to be landed there. They remained on the ships till at length they were taken to England. Four of the twenty ships never reached their destination. One was lost, two were driven by storm to San Domingo, and the fourth was taken by the Acadians themselves, and returned to Acadie.

When peace was concluded between France and England, in 1763, a few thousand of the Acadians started for Canada, where they settled. Three years later, another band having gathered in Boston, about eight hundred persons began the long march by land for their loved Acadie. Men, women and children, with but little food, toiled on through the forests of Maine, and up the Bay of Fundy to the isthmus of Shediac. Four months had been spent on the way, and at last they found that their former homes were in the possession of others, and Grand-Pré was not for them. Here the greater number of them remained, and their numerous descendants are dwelling there today. A small band of fifty or sixty continued round the shores, passing through Beausejour (now Cumberland) Piziquid, and Grand-Pré. Everything was changed. The English had been in the country for six years, and new houses stood where the undisturbed ashes of hundreds of their homes had lain till 1760.

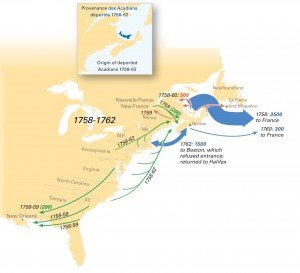

Exiled Acadian routes back to Acadie 1758-1762

“The children were frightened by them, the men and women were annoyed as by a threatening specter from the grave, everybody was angry with them, and the poor wretches dragged themselves from village to village, worried and worn out by fatigue, hunger and cold, and a despair that grew at every halting place,” till they reached Annapolis.

On the deserted shore of St. Mary’s Bay they at last found themselves, having tramped a thousand miles, to be driven to a barren country. “Under pressure of necessity, these unfortunate outcasts raised log huts; they took to fishing and hunting; they began to clear the land and soon out of the felled trees some roughly-built houses were put up. Such was the origin of the colony of the Acadians in Digby County. Here was the home of my [the author’s] ancestors.